On their agenda are missions to the Moon and Mars, and, closer to home, satellites to monitor the weather and encrypt global communications.

The proposed budget for the European Space Agency is a near-25% increase.

Finding the cash will be a challenge, however, given the big rise in the cost of living across the continent.

Governments may well be tempted to pull back on their space spending.

“This is true, but let me say the package we have on the table is found by every member state of Esa to be very attractive,” said agency director general, Dr Josef Aschbacher.

“No-one is saying ‘this is not what we should be doing’, and every country is making huge efforts to find the money, despite the economic situation,” he told BBC News.

Member states of the European Space Agency meet every three years to agree an activity programme and the money needed to fund it. It’s a day-and-a-half of tough negotiations.

All countries have to support science research (€3.1bn is requested, over five years) but for other projects, nations will commit on a voluntary basis. And depending on their interests, they may decide to put in more or less than the figure that reflects their economic weight, or gross domestic product (GDP).

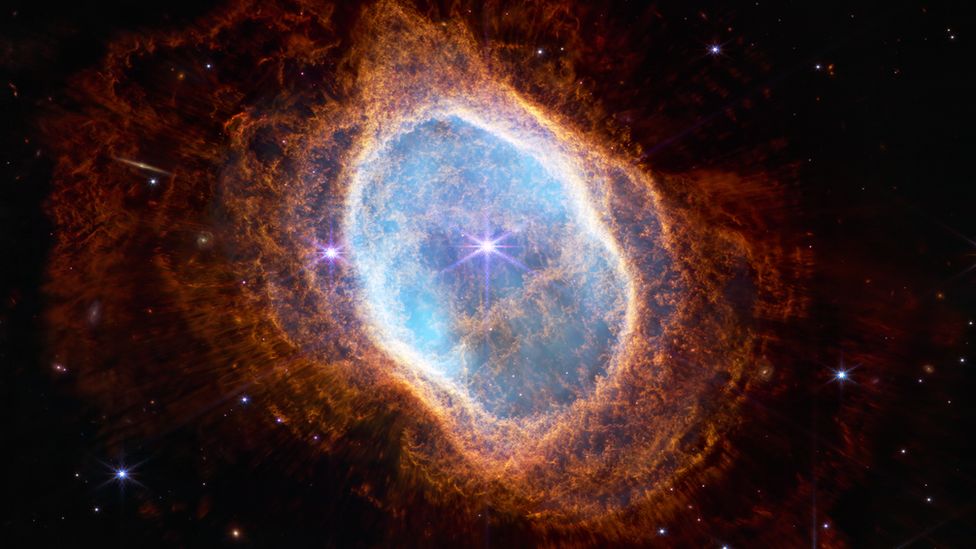

France, Germany and Italy have a particular interest in rockets (€3.2bn), for example. Countries like the UK have traditionally been one of the biggest backers of telecoms projects (€2.4bn), given its manufacturing strength in big satellites. And many want to help build Esa’s Earth observation (€3.0bn) spacecraft; likewise, participate in its human and robotic exploration missions (€2.9bn). Witness the current demonstration flight of the US space agency’s (Nasa) Orion capsule, which passed by the Moon on Monday. This vehicle, which will one day carry astronauts back to the lunar surface, is propelled by a module provided by Esa.

European governments are acutely aware that when it comes to the “space race”, they are falling behind. America and China invest considerably more in their space agencies; and in their commercial sectors, the venture capital available to new space firms dwarfs what European start-ups can access.

Ministers gathered at the Grand Palais Éphémère (GPE) in Paris are sure therefore to focus their investments in the programmes expected to generate the biggest economic returns.

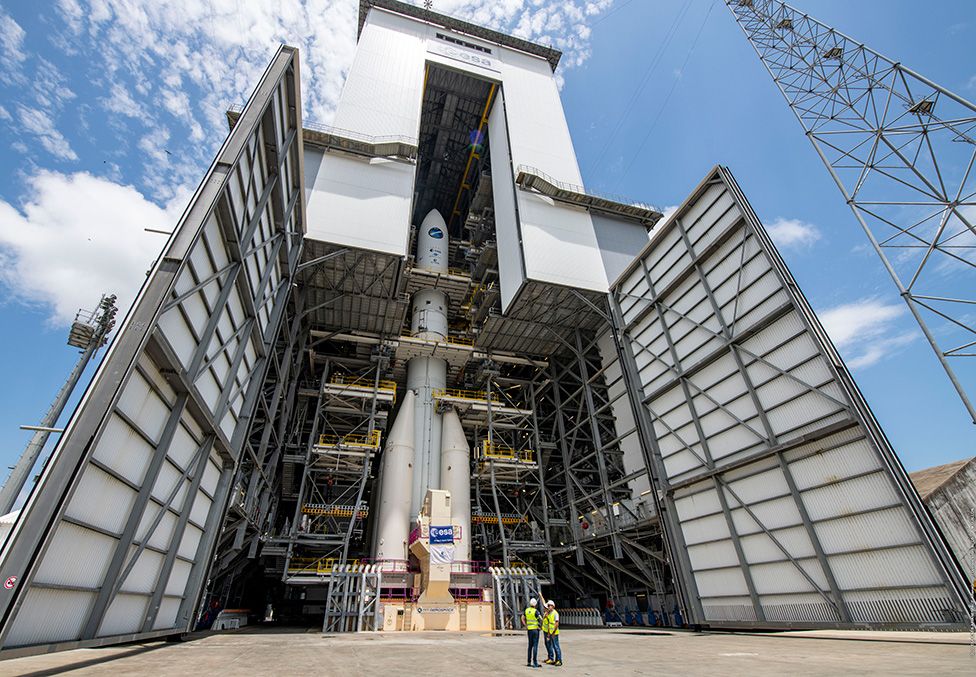

One area where there will be intense negotiation concerns rockets. Europe’s new launcher, Ariane-6, has fallen behind in its scheduled introduction and won’t make a debut until the end of next year at the earliest. That has a knock-on cost, for which the ministerial meeting will have to find €200m of cover.

Another budget line to watch is the €750m requested for the European Union’s Iris2 “secure connectivity” constellation. The European Commission wants to develop a network of broadband internet satellites not unlike the ones being rolled out now by the American entrepreneur Elon Musk and the London company OneWeb, but focussed on government services. Its overall cost will probably nudge €6bn, and Brussels is looking to Esa countries for support.

It’s worth emphasising that that the European Space Agency is not the European Union. They may share member states and cooperate on certain space projects, but they are distinct legal entities.

This is important for the UK, which, since 2020, has not been a part of the Brussels club.

London’s delegation, headed by science minister George Freeman, comes to the GPE conference centre with its own objectives.

Britain has assembled a rover, called “Rosalind Franklin”, to explore the surface of Mars. It’s going to take about €700m to build the equipment needed to land it on the Red Planet, with €360m being requested at this meeting. Mr Freeman will be making a sizeable contribution to ensure the rover fulfils its mission.

He’s likely also to get out the London Treasury’s cheque book for a number of Earth observation projects.

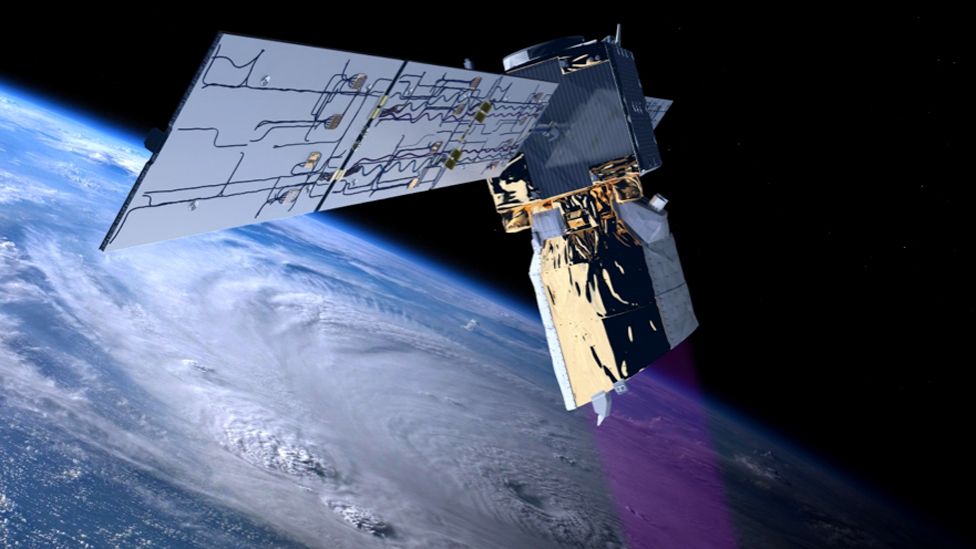

One of these is a satellite called Aeolus to map the direction and speed of the wind across the globe to improve weather forecasting.

The Esa budget line for this programme, which will comprise two spacecraft run in series, is €405m. British industry built the revolutionary prototype that is flying today and very much wants to lead the implementation of the follow-on system.

Negotiations in Paris should wrap up by Wednesday lunchtime. Esa will bring a close to the meeting by announcing the names of a new tranche of astronaut trainees, its first recruits since 2009.