Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party is leading the polls ahead of 25 September elections – and if she wins, she will look to form a right-wing government.

Two months after the collapse of Mario Draghi’s unity government, here’s what you need to know about the main challengers and how Italy’s revamped elections work.

Giorgia Meloni

Four years ago, her party attracted little more than 4% of the vote in the last general election and yet she’s now is in pole position to win, with a possible quarter of the vote. Backed by two other parties, the League and Forza Italia, polls suggest she is heading for a majority coalition in Italy’s two houses of parliament.

Giorgia Meloni, 45, was the only major party leader who refused to go into popular technocrat Mario Draghi’s broad-based coalition, so she was the only big opposition leader when it collapsed in July.

She formed Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia) in 2012, four years after becoming Italy’s youngest-ever minister under Silvio Berlusconi in 2008.

As a teenager, she joined the youth wing of Italy’s neo-fascist movement, formed after the war by supporters of late dictator Benito Mussolini. In her 2021 book, I Am Giorgia, she stresses she is not a fascist, but she identifies with Mussolini’s heirs: “I have taken up the baton of a 70-year-long history.”

Unlike her right-wing allies, she has no time for Russia’s Vladimir Putin and is pro-Nato and pro-Ukraine, even though many voters on the right are lukewarm on Western sanctions. Besides tax cuts, her alliance wants to renegotiate Italy’s massive EU Covid recovery plan and have Italy’s president elected by popular vote. To change the constitution, she would need a two-thirds majority in parliament.

Embracing a controversial old motto, “God, fatherland and family”, she campaigns against LGBT rights, wants a naval blockade of Libya and has warned repeatedly against Muslim migrants.

Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby, yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology… no to Islamist violence, yes to secure borders, no to massive migration

She also seeks a “different Italian stance” towards the EU’s executive body. “That does not mean that we want to destroy Europe, that we want to leave Europe, that we want to do crazy things,” she says.

Enrico Letta

If Giorgia Meloni is to be beaten, it will require a big showing from the likely runner-up – the centre-left Democratic Party (PD) of Enrico Letta. But his hopes of forming a strong, rival alliance with an array of smaller parties suffered a blow when the centrist pro-European Azione (Action) party pulled out, objecting to two of his other partners, the Italian Left and Green Europe.

IMAGE SOURCE,MATTEO BAZZI/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

IMAGE SOURCE,MATTEO BAZZI/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCKEnrico Letta, 56, was prime minister for 10 months in 2013-14 and is no stranger to Italy’s cut-throat politics. He led a coalition with Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and was ultimately brought down by a rival in his own party, Matteo Renzi.

A big supporter of Mario Draghi’s government, Mr Letta said Italians would punish those who brought him down in July, pointing the finger squarely at the populist Five Star Movement under Giuseppe Conte. Mr Letta has found common cause with former Five Star leader Luigi di Maio, who fell out with Mr Conte and formed a new centrist party called Civic Commitment (Impegno Civico).

The centre-left leader’s main goal is to stop the hard right taking power in Italy. He wants investment in renewable energy and proposes an eight-point plan for education under the banner “knowledge is power”.

The PD backs a €9 (£8; $9) minimum wage to cover some three million workers and wants to: make it easier for children of immigrants to obtain citizenship; combat anti-LGBT discrimination and legalise gay marriage.

Italy’s new election system

The winning alliance will need a majority in both houses of parliament, the Chamber of Deputies and Senate, and Italians are voting for both of them.

New rules mean parliament has shrunk by a third, so there will now be 400 deputies in the Chamber, instead of up to 630 MPs, and 200 Senators instead of 315.

Italy has a hybrid voting system, in which three-eighths (about 36%) of members are elected in a first-past-the-post vote in single-member constituencies. The rest are elected by proportional representation according to party lists of candidates, with seats reserved for voters abroad.

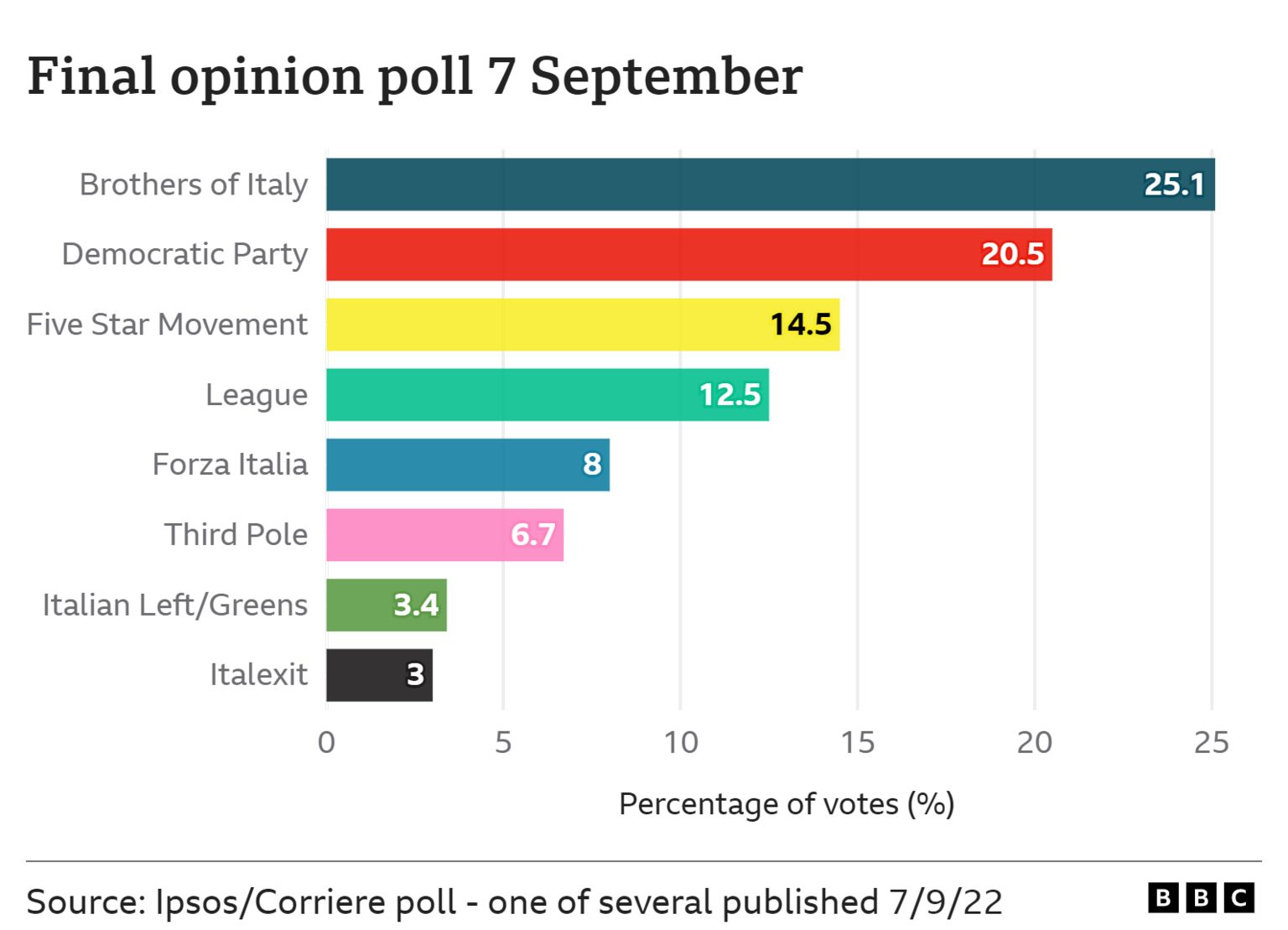

Voters need to be 18 and get one vote for the Chamber and one for the Senate. Parties have to secure at least 3% of the vote to get in, with Italy divided into 27 electoral districts. Final opinion polls were published on 7 September, including this one from Ipsos.

Who else to watch out for?

Conservative right

Giorgia Meloni’s party has no experience in government, so she will need full support from ex-PM Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Salvini, who were both part of the Draghi government. As the end of the election campaign drew close, the three leaders held a joint rally in Rome.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESAlthough he was Italy’s longest-serving prime minister, Mr Berlusconi, 85, is running for election to the Senate for the first time since he was barred in 2013 for tax fraud. His centre-right Forza Italia is seen as the weakest of the three parties.

Matteo Salvini’s League is a natural partner for Ms Meloni. As interior minister, he closed down migrant camps and blocked NGO boats carrying migrants rescued from the Mediterranean from entering port.

What do they want?

They are promising to cut sales tax on energy and other essential items, and to introduce a flat tax for the self-employed, possibly set at 23%, which critics say would give more to the rich than the poor.

They want to end Italy’s ban on nuclear power. There are plans to shore up Italy’s birth rate with increased allowances for families. And they aim to combat irregular immigration and manage legal immigration in an orderly way.

Five Star

Giuseppe Conte’s anti-establishment party won the 2018 election with almost a third of the vote, and while they are still polling at up to 14%, they are not currently part of any alliance.

IMAGE SOURCE,FRANCO CAUTILLO/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

IMAGE SOURCE,FRANCO CAUTILLO/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCKThey began by sharing power with the far-right League, and then switched to the Democratic Party before ending up as part of the broader Draghi government. Dozens of Five Star MPs deserted Mr Conte when he objected to sending weapons to Ukraine.

Under his leadership, their policies have swung to the left. Five Star’s flagship policy four years ago was a citizens’ income for the poor. Mr Conte now supports a €9 minimum wage, wants to scrap a regional business tax and make it easier for immigrants’ children to get citizenship.

Five Star’s ideas are not wildly different from the centre-left, and the two main centrist parties have warned voters that Mr Conte might patch up his differences with Enrico Letta.

Centrists

Matteo Renzi of Italia Viva and Carlo Calenda of Azione have joined forces, aiming to attract votes from both right and left to create a “third pole” alliance.

If they secure more than 10% of the vote, the thinking is they could win over other parties and avoid a Meloni-led government. It is for President Sergio Mattarella to nominate the next prime minister, but he is likely to choose the winning coalition.

IMAGE SOURCE,MATTEO CORNER/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

IMAGE SOURCE,MATTEO CORNER/EPA-EFE/REX/SHUTTERSTOCKThe centrist preference would be to continue the pro-European policies of the previous Draghi government and even persuade Mario Draghi to return as prime minister, although the former European Central Bank chief sounds unenthusiastic.

Like the centre right, they are keen to lift the ban on nuclear power, and like the centre left, they want to import more liquefied natural gas.

Their team includes two ex-Forza Italia ministers, Mariastella Gelmini and Mara Carfagna, who left the Berlusconi party over its role in bringing down the Draghi government.