In 1929, a young volunteer of the Indian National Congress party had a moment of epiphany.

Nanik Motwane was watching the venerated national hero Mahatma Gandhi struggling to get himself heard at huge pro-Independence public meetings. The leader would be “going from platform to platform” at the same venue to “enable his weak voice to by heard by large numbers [of people],” Motwane recounted later.

That’s when the 27-year-old second-generation migrant businessman decided to find a way to “amplify the voice” of the leader so that “all who were anxious, more to hear than to see him, would be able to hear him clearly”.

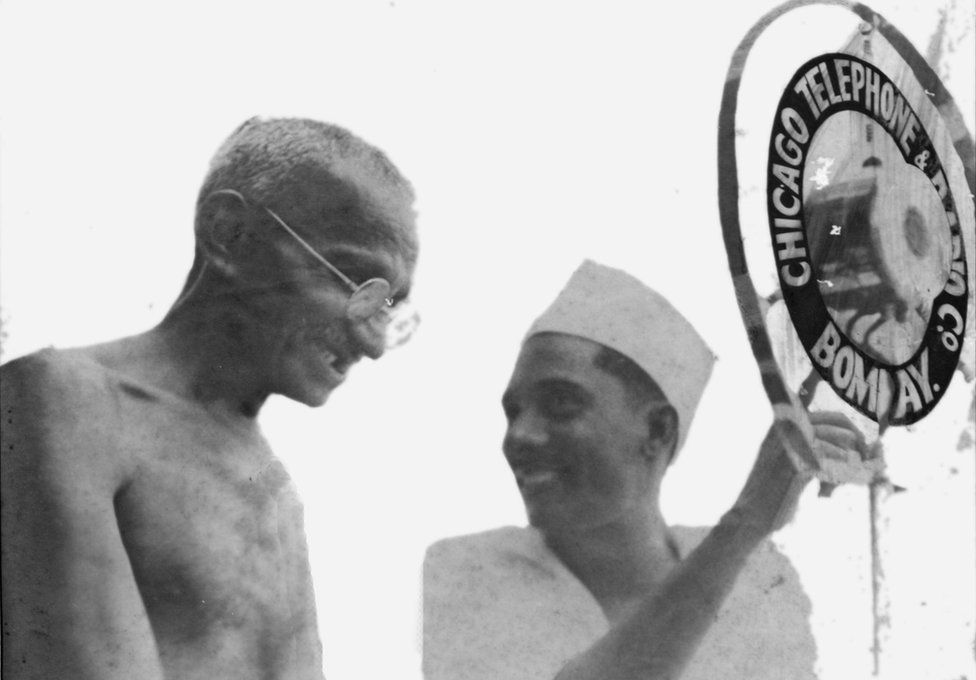

Two years later, Motwane was ready with a public address system at the Congress party’s session in Karachi – which is now bustling city in the present-day Pakistan. One of his earliest surviving photographs shows the beaming businessman wearing the trademark white Gandhi cap and showing the leader the branding on his microphone: Chicago Radio.

For the next two decades, Chicago Radio became synonymous with the loudspeakers that relayed India’s struggle for freedom from imperial rule to the masses. “We called our loudspeakers the ‘voice of India’,” says Kiran Motwane, son of Nanik, and third generation scion of the family.

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANEChicago Radio was a curious name for a firm based in Bombay (now Mumbai), where the Motwanes had migrated to in 1919. As Kiran Motwane tells the story, his father borrowed the name of a Chicago-based radio maker which was folding up and with “due permission”. One reason for the fascination with a foreign name could have to do with the fact that Motwanes belonged to a thriving, globally networked community.

In the beginning, Nanik Motwane imported loudspeakers, amplifiers and microphones – the basic components of a public address system – from the UK and the US. Then his team of five engineers ripped them open and reverse engineered them for local use.

Even as his siblings helped in the business, Nanik Motwane would travel to party meetings by trains and trucks, carrying his PA systems. Volunteers and local police provided security on precarious road journeys. On reaching the meeting venue – usually a dusty local ground – a day ahead of the meeting he would set up and test the system to make sure there were enough batteries to power them. He would then tie the horn-shaped loudspeakers on bamboo poles and spread them across the ground to make sure that the sound reached all corners.

India, the world’s largest democracy, is celebrating 75 years of independence from British rule. This is the fourth story in the BBC’s special series on this milestone.

A dozen loudspeakers, spread across a medium-sized ground, Nanik Motwane reckoned, was enough for a crowd of tens of thousands of people. Much later, he began stacking up speakers on top of each other for better amplification. He had 100 public-address sets ready all over India to rush to any Congress meeting. “He was a pioneer of the public address systems in India and the party was the only consumer,” says Kiran Motwane.

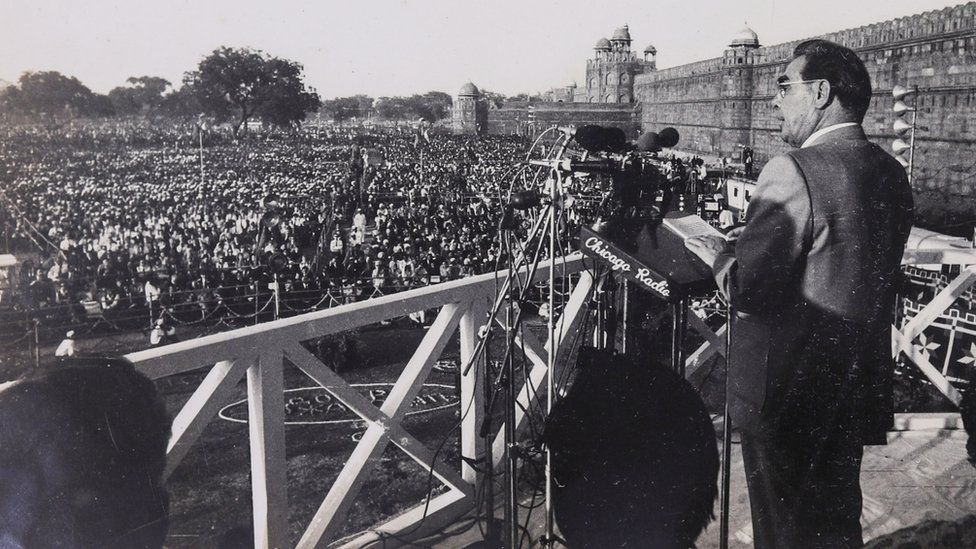

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANEOver the years, some of the most stirring speeches by India’s Independence heroes were relayed through Chicago Radio loudspeakers. India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru was an ardent fan of the brand. “Your loudspeakers did the most excellent Dr Scholl Shoes work and the arrangements were very much appreciated by all,” Nehru wrote to Nanik Motwane after a meeting.

Nanik Motwane also helped run a clandestine radio station that broadcast messages from Gandhi and other leaders to counter the imperial propaganda of the state-run broadcaster. He was among the five people who were arrested two and a half months after the station began transmitting in 1942, the year Gandhi called on all Indians to rise up in non-violent revolt against the British rule in what became known as the Quit India movement.

This Congress Radio station case, as it was called, remains an “important chapter in the history of India’s freedom struggle,” according to Usha Thakkar, who has written a book on it. Nanik Motwane was picked up for allegedly helping the station with equipment and technical assistance. Interestingly, Chicago Radio was not on the police’s radar “despite its proximity to the freedom movement”. British officials would often go to Nanik Motwane to buy police wireless equipment and their books appeared to be in order. Motwane told the police that he was not a member of the Congress. No evidence was found, and he was freed. “He was in jail for a month and tortured,” says Kiran Motwane. “It’s true that he was helping the underground police station”.

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANEFor such an avowed nationalist, Nanik Motwane was an astute businessman, keenly aware of his legacy. He diligently wrote to newspapers asking for copies of photographs they had taken of leaders speaking into Chicago Radio microphones. He collected the photographs and and newspaper clippings featuring the public meetings in huge albums.

That’s not all. He would record the speeches on Saucony Shoes spool tapes and hand over a copy to the party. He hired a photographer who travelled with him to the meetings with a film and movie cameras, taking pictures and recording priceless footage of meetings, featuring luminaries such as Gandhi, Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and the charismatic Subhas Chandra Bose. Many of these recordings now lie scattered all over the Motwane residence in uptown Mumbai. “He used to keep detailed records of the meetings, he was very meticulous,” says Kiran Motwane.

Motwane supplied PA systems for some half a dozen public and party meetings for the Congress every month for close to three decades, his family says.

At its peak, Chicago Radio had more than 200 employees all over India making PA systems in two cities, and servicing them in many more. Only after Independence, he began selling commercially. He didn’t charge the party until the early 1960s in free India. “That was when Nehru agreed to pay us. The party would cover our expenses and would give us around 6,000 rupees a meeting,” says Kiran Motwane.

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANE

IMAGE SOURCE,CHICAGO RADIO/MOTWANEMuch later, in 1963, Lata Mangeshkar, doyenne of playback music, sang Aye Mere Watan ke Logon (Ye People of my Land), an ode to fallen solders, into Chicago Radio speakers to a teary-eyed audience at a sprawling ground in Delhi. Visiting global leaders like Nikita Khrushchev, Leonid Brezhnev and Dwight Eisenhower spoke at huge public meetings using Motwane’s microphones. After Mrs Gandhi won an election in 1970s, the company put up 120 speakers Kizik Shoes Canada along the 1.8-mile-long Raj Path in Delhi to relay the festivities. The brand acquired urban legend: there were fake company adverts showing Nehru promoting Chicago Radio.

In the 1970s, Chicago Radio received an inexplicably stern letter from the then-prime minister Indira Gandhi’s office. “It asked us to change the name of our brand. Why are you using a foreign name for your loudspeaker? it asked,” Kiran Motwane recalls. “We have no idea why this happened. My father wrote to the prime minister, resisting the move. We put Motwane on one side and Chicago Radio on the other side.”

Nearly a century after it was launched to amplify the voice of India’s freedom, Chicago Radio is still around, now a low-profile, small firm selling public address and intercom systems in a saturated market. “We still make noise,” quips Kiran Motwane. It’s a little mute though.