“What I find challenging as an entrepreneur is this idea of narrative fallacy,” Missy Park, founder of athletic clothing company Title Nine, tells Entrepreneur. “All of these things happen to us, which may be related or unrelated. They may be because of our agency or because of happenstance. But at the end, we tie them all up in a bow and say this is how it happened, when it really didn’t happen that way at all.”

Park’s journey can’t be easily tied up with a bow, but the founder says it’s the result of a “cascading set of opportunities” set in motion, fittingly, by Title IX: the U.S. federal civil rights law that passed when Park was 10 years old in 1972 — and after which her company is named. Title IX, which celebrates its 50th anniversary today, prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other education program that receives federal funding.

“In 1972, I’m in a small town in South Carolina,” Park says. “Let me tell you, young women were not playing a lot of sports. And the two or three of us that were, were tomboys. And when Title IX came about, I moved from being a tomboy to being an athlete — just an athlete.”

That ability to be “just an athlete” was pivotal. As a child and teen, Park witnessed blatant sexism towards women athletes, though she didn’t necessarily recognize it as such at the time. She recalls watching the Battle of the Sexes match between tennis stars Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs at a party where adult men wore little pig snouts to signal they were male chauvinist pigs. “And they owned that,” Park says. “They were super proud of it. I mean, can you imagine that now?”

Despite the pig snouts, at the time, Park was struck by the fact that the men were there to watch a woman play tennis. “You can look back on that with the lens of the 2020s, Clarks Shoes at all of the disgustingness of it,” she says. “Or you can look at it like I did as a kid: It’s like, ‘Wow, here is Billie Jean King, an athlete and a leader who has a point of view.’ Even though, clearly, she didn’t see me, I felt seen.”

Park marvels at how lightly King wore, and still wears, that mantle of leadership, refusing to let the anger she must have felt, living in the world she lived in, paralyze her. “She was leading not just for herself, but for a whole movement,” Park says.

King, who first encountered gender inequality when she was 12 years old and was not allowed to join a group photo of junior tennis players because she wore shorts instead of a skirt, has spent decades crusading for women’s equality in sports — even testifying on Capitol Hill on behalf of Title IX. And that Battle of the Sexes match against Riggs? Ninety million people worldwide watched her defeat him 6-4, 6-3, 6-3.

“Title IX did not change the hearts and minds, but it did change the law.”

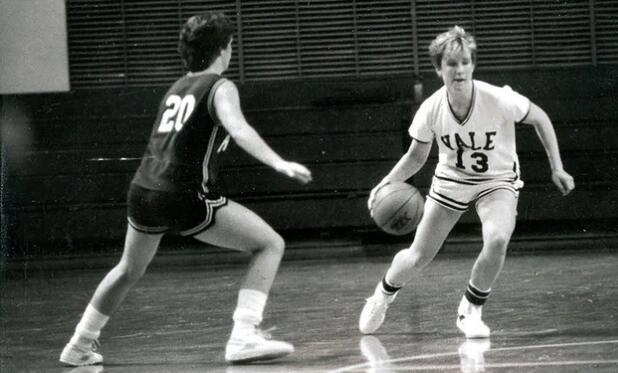

Slowly but surely, Title IX began to change things for women in sports. “All of a sudden, our local university had a women’s basketball team,” Park says. “So I could go and see them play, and it was like, ‘Oh, wow. There are other women like me.’ There were so many teams that I could play on. Being from a small town in South Carolina, I could go to Yale like that.”

But Title IX didn’t shift the prevailing dynamic overnight. “At first, women weren’t ready to play sports, so in some places, there were almost more opportunities than there were women. So as really a sort of average athlete, my timing was impeccable,” Park laughs. “In college, I was able to play basketball, lacrosse and tennis. So for me, I would say that Title IX did not change the hearts and minds, but it did change the law. And at that time, that was enough for me.”

When Park attended college, however, those persisting inequalities became more apparent. Though she and other women athletes were allowed to compete, the playing field was still designed to accommodate men first and foremost. “Yes, we could play on the basketball team,” Park explains, “but our uniforms were hand-me-down men’s uniforms, our practice times were the times men didn’t want to practice.”

One of Park’s teammates, who wore a size seven-and-half women’s shoe, had to shop for basketball shoes in the boys’ department at Macy’s, and it wasn’t long before she and her friends realized that even the bats they were given to play softball were actually baseball bats —Hokas Shoes built for men who might weigh anywhere from 30-50 pounds more. Of course, the inequality extended beyond unsuitable gear and equipment.

“The coaches, both for historical reasons and because hearts and minds had to change, were barely older than we were,” Park says. “Part of it was because there was no pipeline of women’s coaches coming up, but part of it was they were going to pay the women 5% or 10% of what they paid the men.”

Frustrated by the lack of resources allocated to women’s sports, Park and her college friends discussed getting “real jobs” for the short term after graduation, then reuniting to start the women’s version of Nike. “Of course, everybody went out and got real jobs that paid them real money, and I was the only one that was left,” Park laughs.

“No one would come up with this name really, except for me or someone in my generation.”

Park might have been the only one of her friends left with that entrepreneurial fire, but that didn’t stop her from pursuing her goal: She was going to launch a women’s athletic wear brand. At the time, few women business leaders had set out to do the same. Park recalls the women’s brand Moving Comfort, founded by Elizabeth Goeke and Ellen Wessel, and Jog Bra, now Champion, founded by Lisa Lindahl, Hinda Miller and Polly Smith. In fact, it was Goeke and Wessel who gave Park her first lucky break. “They took a chance on me when I was 26 and opened me on net 30 terms, and I had $1 in my bank account,” Park says.

As serendipitous as Title Nine’s name now seems, it was far from the clear choice in the beginning. “As an entrepreneur — and I know this because we’ve had to name things over and over and over again — you think you have to come up with the perfect name, and that ends up being a self-imposed roadblock,” Park says, adding that so often, once entrepreneurs land on a name, it ends up becoming the perfect one.

“The naming of Title Nine was, maybe, one of those real and imagined roadblocks,” Park continues. “I went through probably five or six different names. I was like, ‘Oh, Cheetah Sports’ — because the female cheetahs do the hunting. I had all of these names, and Mervyn’s had Cheetah already, and I kept coming up with ones that were clearly not that original, because they were all taken, and this was even before people were trademarking every name known to man. And I still couldn’t come up with an original idea.”

Park cites Nike as a prime example of the naming conundrum that, ultimately, becomes a non-issue for most businesses. “It was actually technically a horrible name,” Park laughs. “No one knew how to pronounce it. No one knew what it was.” The logo wasn’t much better; Nike’s co-founder, Phil Knight, reportedly paid graphic design student Carolyn Davidson $35 for the image in 1971, despite not loving the design initially — but it’s since become the ubiquitous Swoosh still in use today.

For Park, the naming of her own company came down to a chance encounter at long-standing Berkeley bookstore Moe’s Books, located on Telegraph Avenue. “I picked up this book, and it was about the women’s movement, and I was just paging through it, and there was this whole section on Title IX,” Park says. “I was like, ‘Ah, that’s it.’ And once I’d named it that, it was like, ‘Oh, this is it.’ No one would come up with this name really, except for me or someone in my generation — I was 26 at the time.”

Since then, the name Park stumbled upon all those years ago has not only defined the company in terms of its connection to Title IX — and what its passage meant for women athletes in 1972 and now — but has also helped guide the company’s course when it comes to ongoing issues surrounding women’s equality. “It is inherently political,” Park says of Title Nine’s name. “Although I don’t consider myself a hugely political person, Title IX the law was so personal to me. We don’t get involved in all things political, but when there’s something that is deeply personal, the name has really helped inform how we approach our business decisions.”

Most recently, the name helped Title Nine determine its response to the leaked Roe v. Wade decision; the company chose to put potential sales impacts aside and released a statement that discusses reproductive justice.

“The only level playing field I might play on would be one of my own making.”

When it comes to attitudes towards women and women leaders, and the areas still most in need of improvement, Park points to ignorance as the greatest barrier to progress, citing an example from the Nevada legislature, which debated over a 2019 bill that would allow people access to a year’s supply of birth control. Nevada’s legislature has more women than men in both chambers, and when male legislators pushed against the bill, claiming women would sell the pills if given that many upfront, Senator Pat Spearman posed the question already obvious to the many women in the room: “Why would they sell them if they need them?”

Park says such ignorance prevails because men don’t understand the full scope of women’s lived experiences — and vice versa. “We haven’t walked a mile in each other’s shoes,” she says. “I don’t know what it’s like to walk through the world feeling like it is my job to not only support myself, regardless of whether I want to be an investment banker or a stay-at-home dad. I don’t know what it’s like to walk like that. But I can damn well tell you that they don’t know what it’s like to live with the responsibility and the promise of getting pregnant every single day of your life.”

It’s a real issue that inevitably makes its way into the business world too, Park explains. “If you’re going to go out and pitch to investors, you’re going to walk into a room of people who have not walked in your shoes,” she says. “And I don’t want to call that discrimination, although it can be that, but it’s also just plain ignorance. And I’m not excusing it for that, but there’s so much intent with discrimination, whereas with ignorance, there’s a little bit of laziness maybe, but it’s not as nefarious as intent.”

The key to mitigating that problem, Park says, is ensuring that women have as many opportunities to lead as men do. She calls that approach an “antidote to ignorance” and believes that starting a business can have a similar impact. “I really think founding your own business is an antidote to discrimination,” Park says. “We [Title Nine] as a company feel it’s an antidote to discrimination. It’s our little place where we can build this business around women owning and risking and leading in every aspect of the company, even finance and computers — all of it.

“Coming of age during those hard hard-fought early years of Title IX — that was enough resistance for a lifetime for me,” Park continues. “It really was enough Thorogood Boots resistance to make me realize that the only level playing field I might play on would be one of my own.

Park is committed to leveling that playing field for all of Title Nine’s team members too, and that includes making sure that its executive leadership fully understands the business fundamentals for success. “At GAP, no one understands a P&L and a balance sheet,” she says. “No one does, not one person there. You could go up to almost the highest level of the business and they won’t understand it, but for me, a fundamental part of our work is to make sure that [Title Nine executives] do — because if you don’t understand a P&L and the balance sheet, then you’re going to lose your business.”

That business education from the inside out is part of Title Nine’s strategy to give women the tools they need to go as far as they’d like to go. “We want women to own,” Park adds. “And we are made better by that.”

“There’s no ownership without risk.”

Title Nine is on a mission to cultivate women leaders beyond its doors as well. It wasn’t long before the company recognized that it was primarily doing business with other big companies, and even though those companies were committed to the advancement of women, they were lacking in non-straight, non-white, non-male representation. Title Nine’s thick vendor manual was contributing to the problem: Many smaller, women-owned businesses, still in the process of bootstrapping, were unable to comply with its policies and procedures.

That realization was the genesis of the company’s annual Pitchfests, Park says. Title Nine’s Pitchfest Outdoor Edition invites women entrepreneurs to share their stories, pitch their products and join the Title Nine community of Movers and Makers. The winners earn a purchase order from Title Nine, a feature spread in a 2023 Title Nine catalog and on the company’s website, and brand-building exposure.

The Pitchfests help Title Nine put its own values back into the world and ensure the company gets to continue to work with women-owned brands doing exciting things. “Quite frankly, I think it fills all of us up to do business with them, because they’re so close to the product,” Park says. “You see bad-ass mountain bikers at Wild Rye, and this great flock of women runners at Oiselle, and they’re really fun to work with. Nothing against North Face, but it’s kind of corporate.”So the thing for me, is it’s a virtuous cycle,” Park continues. “We hope that we can help them remain independent as long as possible, because that is really it: Ownership is critical. There’s no ownership without risk. There’s no ownership without leading, and there’s really no risk unless you own. So those three verbs are really critical for us and are hopefully fostering some of the change that we hope will happen in the world at large.”

Earlier this year, Title Nine also launched its first annual Pitchfest Girls program, which gives young women ages 11-17 the opportunity to tell their stories and share their product ideas for the chance to win $500 cash funding for their businesses. Additionally, the company recently kicked off its Pitchfest Nonprofit Edition, which funds women leaders in the nonprofit sector.

“Momentum cures all ills, if you just go fast enough.”

Since its 1989 founding, Title Nine has bootstrapped its way to a team of approximately 300. Park says the company has been able to avoid a large corporate buyout and outside investors because of the many inside investors lending their support over the years.

“I think it’s really important for entrepreneurs to recognize that there are a lot of banks out there,” Park explains, “and there’s a lot of different kinds of investors. The subscription model is one way; gift cards are another. There are a lot of ways that both customers and suppliers can be investors.”

But Park also credits her entrepreneurial success to the drive that comes with being committed to her purpose. “Give me a ‘why,’ and I can get through any ‘how,'” she says. That “why” behind the “how” was recently put to the test by the Covid-19 pandemic. As a retailer, Park says, Title Nine relies on cash flow, and the company had just six weeks of cash on hand when the pandemic hit. Eventually, it reached the point where it wouldn’t be able to pay its suppliers. But Park and her team were determined to forge a path forward.

Everyone at Title Nine took a pay cut, and those cuts went to the suppliers. Park told the suppliers the company was short on cash and couldn’t pay them more than it was paying its employees — but that it would continue to pay all of the women-owned and led businesses it worked with in full. “Because there’s the whole ‘why’ again,” Park says. “And everybody got it.” Ultimately, everyone was paid back in full — the suppliers and the employees who’d taken the temporary pay cut.

To aspiring women entrepreneurs ready to take that leap towards their own “why,” Park says the key is to simply get started, no matter what that might look like, and then keep up the momentum — owning all the while. “Hold on to ownership and hit singles, hit singles,” Park says, “because if you strike out, you’re on the bench. Just hit singles, get on base. I don’t care. You can take a base on balls. This is a softball analogy, I want to say,” she laughs. “It is not a baseball analogy.”

Park adds another helpful lens, this one inspired from her mountain biking experience: “I always say, ‘Momentum cures all ills,’ if you just go fast enough. There’s limits to that — there’s no amount of momentum that’s going to get me through a brick wall, but as long as you choose your obstacles carefully, momentum cures all ills.”

“We’re going to use Title IX as an opportunity to hold up a mirror to women athletes everywhere.”

Today marks Title IX’s 50th anniversary, and although the milestone holds personal significance to Park, and to the Title Nine team, the founder also struggles with relegating the celebration of women’s achievements to certain months and days — when they deserve our full attention no matter the time of year.

“It is Women’s Day 365 days a year, 24 hours a day,” Park says.

But the company will mark the anniversary of its namesake with a social media campaign, in collaboration with Oiselle, that goes beyond the lip service many other brands will pay to the occasion. The company invited 50 women to tell their sports stories and encouraged them to tag other women athletes who can share their own stories, perpetuating another kind of virtuous cycle that gets at the heart of Title Nine’s mission. The campaign began on June 1, with captions including #MySportStart, and will culminate on June 23 with a finale of photographs gathered over the month.

“A lot of the time, I think with women, we still don’t see ourselves as athletes,” Park says. “We may run, but we don’t see ourselves as a runner or a marathoner. We may play soccer, but we’re not a soccer player. So it’s having women see themselves as athletes — that’s what we’re hoping to do.

“Men see stuff in themselves that literally no one else in the world sees,” she continues, laughing. “It’s just like, ‘Okay, yeah, well sure.’ Whereas women are the exact opposite. Everyone sees it before we see it ourselves. So we’re going to use Title Nine as an opportunity to hold up a mirror to women athletes everywhere.”