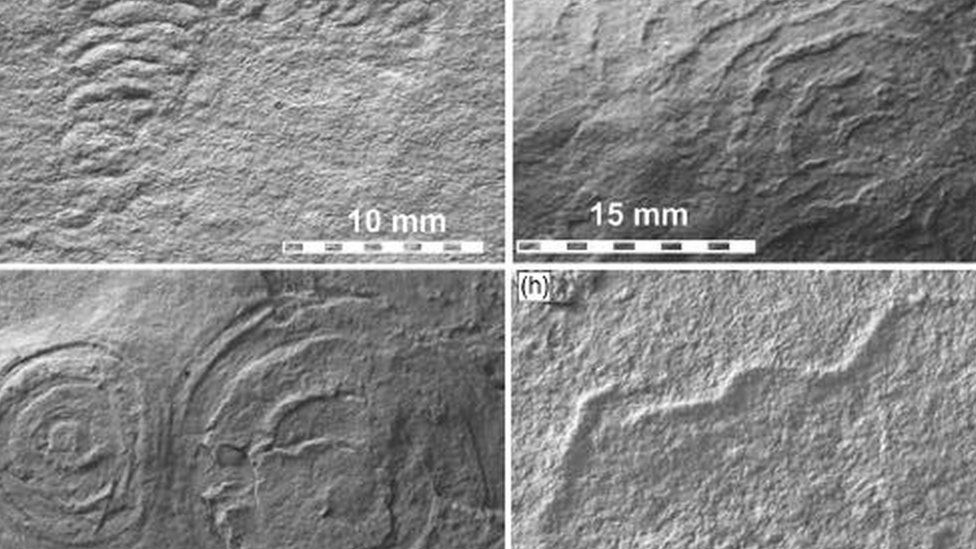

Welsh rocks have revealed details about some of Earth’s earliest creatures.

Fossils first discovered in Carmarthenshire in the 1970s revealed traces of organisms that have now been dated to 564 million years ago.

The ancient disc-shaped invertebrates probably lived in shallow waters along the coast of volcanic islands.

Researchers say the organisms – too primitive to be described as animals – are “completely unlike any other forms of life”.

The research findings, which have taken decades to complete, have been published in the scientific Journal of the Geological Society.

The fossils were first discovered in 1977 at a quarry near the village of Llangynog, Carmarthenshire, by Prof John Cope.

They were quickly identified as being exceptionally old and important, but Prof Cope said he waited decades to find out their exact age, which hampered further research.

The breakthrough came when a method, which measures radioactive decay, dated the fossils to 564 million years ago, plus or minus 700,000 years.

They come from the Ediacaran period, when the first multi-cellular organisms – meaning organisms made up of multiple cells – existed on Earth.

‘We just don’t know what they are’

Prof Cope, from Swansea, said of the organisms: “They are multi-cellular but we just don’t know what they were. They are completely unlike any other forms of life.

“We’ve known for a long time that these fossils were the oldest in Wales and then, in 2000, a scientist who had been working in Newfoundland on similar fossils looked at them and said ‘they’re exactly the same’.”

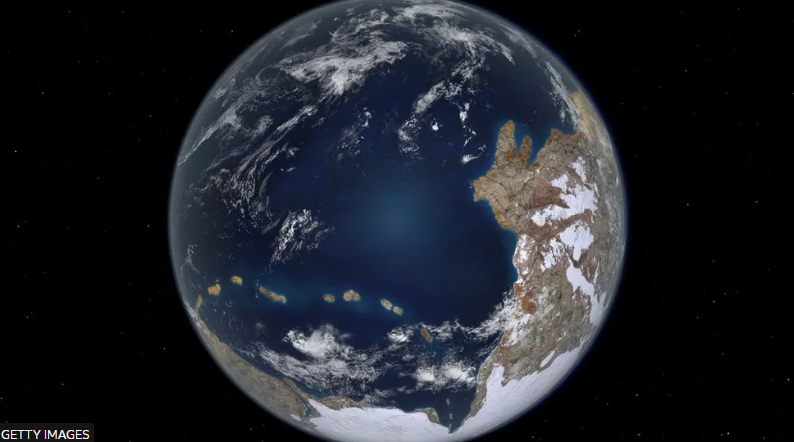

During the Ediacaran period, Wales was part of a micro-continent that geologists called Avalonia.

Newfoundland, in Canada, would have been a neighbouring area.

Over hundreds of millions of years, the creation of the Atlantic Ocean split Wales and eastern Newfoundland thousands of miles apart.

The breakthrough in dating the fossils was due to the work of the lead author of the paper, Pembrokeshire-born PhD student Tony Clarke, who has been working on radiometric dating at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia.

Mr Clarke has also dated some of the rocks that became the megaliths of Stonehenge.

As a co-author of the paper, Prof Cope, formerly of Cardiff University and now a research associate at Bristol University, said the work had been a major breakthrough.

“These dating techniques have improved so much over the years and they are now so accurate,” he said.

The Llangynog fossils are held at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff.